What follows is an excerpt from a larger work covering my family history. I thought it might be interesting for current Navan residents to read about some of the areas that were once “wild” but now covered with houses.

I recently read a book called The Big Year subtitled A tale of man, nature and fowl obsession, the story of three men and their struggles and adventures as they competed against each other to be the one to see more kinds of birds north of the U. S. – Mexico border than anyone else had in the space of one year. All of them managed to surpass previous records. Their obsession drove them through many risks, hardships and financial cost.

When Kathryn and I were discussing The Big Year and the three men, we decided we had never experienced such an obsession, fortunately. On thinking it over later I decided that the closest I had come to even a shadow of obsession was during my first years of bird watching. In 1954 I was twenty-six and living in Navan, a small rural village fifteen miles east of Ottawa. It was the spring of 1954. Judy was four and Andrew was about sixteen months old. I had started reading a book I had found in Book-of-the-Month’s monthly catalogue. [Living in Navan, where there was no bookstore and no library and only infrequently visiting Ottawa, I was grateful for Book-of-the-Month and the access and information it provided about recent publications. Books were less expensive than today and seemed within my ability to buy provided I remembered to send back the necessary referral slip for those selections I didn’t want.]

The book, written by Dorothy Edwards Shuttlesworth, was called Exploring Nature with your Child: an introduction to the enjoyment and understanding of Nature. The book described birds, animals, fish, insects, flowers, trees and went on to explain the planets, the stars and the weather, all in an enjoyable yet authoritative manner. As I began to read the chapters on birds and bird watching I realized that there were more varieties of birds in my backyard than I had ever imagined. Our house was located on the main street of the village, but the property ran through to the street behind, which in the fifties was a grassy track. Our garden ended halfway back and the rest was trees and small bushes with a path running through. One giant pine tree stood above everything else.

I eagerly read Chapter 3, “The Delightful Hobby of Bird Watching.” It assured me that it was a hobby that could be enjoyed by all ages without special equipment but good binoculars and a pocket guide to the birds added to the enjoyment.

Everyone knows a robin, a crow, an English sparrow and a pigeon. Of course to a bird watcher the common pigeon is a rock dove. It looks more impressive on your list. Some people notice the difference between a grackle, a starling and a red-winged blackbird; to others they are all black birds. I once visited the Mer Bleue Bog (a conservation area between Ottawa and Navan) in the fall when thousands of redwings had gathered and were perching on the reeds and bushes. Their noise was almost deafening, like a million rusty gates being opened at once.

The first new bird I recognized in our yard was a little brown house wren flitting about an old pile of brush and logs behind our garden. I knew it wasn’t a sparrow because its little tail stuck straight up when it perched on the log.

Most of the birds I was able to recognize that year I found on trees and shrubs around the village or on the neighbours’ lawns like the first meadowlark I spotted with its prominent black V on its bright yellow breast.

It added a great deal to my enjoyment to notice the kingbirds sitting upright on the fences and telephone wires and to identify the nighthawks diving high overhead for insects in the evening.

In the fall I acquired my first copy of Roger Tory Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds…east of the Rockies. Just in time to identify some of the birds that visited only in the winter. On November 1 a large flock of Evening Grosbeaks settled on the Manitoba Maples behind the garden and began eating the maple keys. I was hanging clothes in the backyard, with Judy, four, helping me when we noticed them. You could hear them cracking the keys with their large white bills, and the males with their yellow, black and white plumage were unmistakeable. They stayed several days and didn’t leave until the seeds were gone.

That Christmas my favourite gift was a pair of binoculars. They became a treasured companion and we all enjoyed the new improved views of the birds. On December 27th four rosy coloured Pine Grosbeaks appeared sitting in a ditch eating weed seeds across from the Orange Hall. They had a sweet thin little voice. The Pine Grosbeaks brought my total for the year to twenty-two. By the end of the next year I was disappointed if I only saw that many in a day. How our expectations grow!

I started keeping a life list of birds on October 1, 1954 about the same time I acquired my field guide. The field guide had a Life List that could be ticked each time a new bird was seen but I used a scribbler (a lined 8 x 11 notebook with a picture of a sailing schooner on it). I noted the date first seen and where I’d seen it. The first dated bird noted in it was a hairy woodpecker seen by Judy and me on a tree in the bush behind our garden, October 1, 1954.

1955 started off very auspiciously on January 21st when Judy, Andrew and I saw a saw whet owl, not in the wilderness unfortunately, but in Elsie Clarke’s living room. Elsie was our village postmistress and when I went to collect our morning mail she asked us to come through the store into the living room to see what one of the school children had left with her that morning. She thought it was a barn owl. Thanks to my new field guide I was able to identify it.

The saw whet owl is one of the smallest owls, 7 ½ to 8 inches high. Peterson describes it as “a tiny absurdly tame little owl.” The child walking to school had noticed it sitting in a bush. It should have been off to Louisiana or Virginia for the winter but when I saw it Elsie was trying to feed it bits of raw meat and water and it was sitting quietly in a box. She found a temporary home for it with a local man who kept exotic birds.

Winter wasn’t a good time for bird watching in our area, although as the books all tell you there are fewer confusing birds around so it is easier to be sure of your identification of those you see. I managed to add six new birds to my list during February and March. By this time I was taking the field guide and the binoculars each time we went out in the car. We watched a Canada Jay near Sarsfield as it crossed and re-crossed the road, stopping several times to let us all see it as we followed it slowly along the road. Next we saw a northern shrike in a hawthorn tree on the road to Ottawa and a horned lark on the Smythe Road. The horned lark is one of the harbingers of spring and returns in the middle of February when the snow starts to leave the gravel at the edges of the road.

One Monday morning in February I looked up from the washing machine to see a Hungarian partridge walking through the backyard. Now we call them grey partridges and they look somewhat like very small grey chickens with a rust coloured tail that shows when the bird flies. They burrow into the snowdrifts during a storm and when it is over, look for weed seeds and leftover grain. I hurriedly put on my coat and followed the partridge through two neighbours back yards until it disappeared in the bush, never once flying.

During the winter I bought two more books about birds. The first was Birds of Canada the 1953 edition by P. A. Taverner. It would tell me more about the birds I saw than the field guide provided. Birds of Canada, which was published under the authority of the National Museum of Canada, describes the general family to which an individual belongs and then describes the individual in detail, its nesting habits, its economic importance and whatever facts Taverner found interesting. Some of his descriptions were almost poetic, he so delighted in the birds. For example, listen to his description of a small, long legged shore bird that nests on the prairies, a Wilson’s Phalarope:

One of the commonest as well as one of the loveliest of the inhabitants of the prairie sloughs. It loves the little sunny mud-bottomed pools of shallow water in the meadow. While the males, in grass-shaded nests, are performing the duties of incubation, the females, in little friendly parties disport themselves with exquisite grace on nearby open water. They swim about like blown-thistle-down, their white bodies riding high breaking up the smooth surface into innumerable interlacing lines of silvery ripples.

How could I not want to discover such a fascinating bird. However, when I finally did see a Wilson’s Phalarope the setting was quite different. It was in mid-August, 1980 and it was feeding on a marshy beach on Grand Manan Island in the Bay of Fundy. The bird was far from its prairie nesting grounds, among hundreds of other shore birds beginning their migration to the south.

The second book I bought that winter was The Birds of Brewery Creek by Malcolm Macdonald. The British High Commissioner in Ottawa from 1941 to 1945, he had lived at Earnscliffe on the Ottawa River. He had begun bird watching when he was a boy in Scotland and continued in Ottawa during any free time in his busy days, mostly in the early mornings. In 1944 he discovered the mouth of Brewery Creek, almost directly across the river from Earnscliffe on the Hull side. He began exploring it in his canoe and was delighted to find it, in his words, “a pleasant haven inhabited by some interesting birds.” There was a variety of habitat along the mile long creek, the only signs of civilization were two or three small cottages inhabited by men who tended log rafts during the summer. The brewery from which it had drawn its name had disappeared years before.

Malcolm MacDonald decided to keep track of the number of birds he saw within its borders during 1945. The book is arranged by month. During February and March he crossed over on skis and on snowshoes several times, the final time was on March 11th. By March 21st spring break up had come and he canoed across for the first time that year. His final canoe trip for the year occurred on December 11th. During that period he saw 160 birds.

His close observations of the birds’ activities and the humour with which he wrote, as well as his persistent pursuit of bird watching served as an inspiration for me and I could hardly wait for the return of the various species.

At the end of January, I had begun going out on snowshoes in the early morning on Sundays and other days when Herbie was home to look after Judy and Andrew. I followed a winding path through the bush with a clearing at the centre usually seeing only chickadees, starlings and blue jays but I had a “wonderful time” as I wrote in the little nature notebook I had started to keep. I enjoyed trying to interpret the various tracks I found in the snow. Rabbit tracks were easy to spot, especially when found near a heap of their tell-tale little balls or a freshly chewed branch. The chicken-like tracks of the grouse could be seen sometimes accompanied by wing marks. One morning in late March I thought I smelled a skunk and saw fresh animal tracks. I bent to look at them when a large bird flew up from a bush less than a foot away. We both scared each other. As it flew across the open space, I could see its barred tail and its reddish-brown colour, my first ruffed grouse.

Finally, spring arrived and I woke up at the sound of the first birdcalls. The first red wing blackbird had arrived on March 20th and on March 31st a robin and a grackle. But when I tried to go back through the bush on April 1st and 2nd I couldn’t because I sank in the very soft snow and the ditch I usually crossed was filled with water. It took two long weeks before I could get across the ditch and back to the bush again. However, the number of birds around the house kept increasing daily. The song sparrows arrived, and the juncos came in flocks providing lots of opportunity to watch their actions and hear their songs. Judy, Andrew and I saw a vesper sparrow on the grassy lane behind the house and we all saw and heard our first killdeers in an icy field on the Heron Road. They really do say their name quite loudly and often and are also easy to identify by the two black bands on their chest.

On April 16th my notebook says:

Sunday morning and I finally reached the creek through the bush. It was my best walk yet. During the day I saw nineteen kinds of birds, five new kinds. I also saw what I’m sure was a loon flying overhead. It was making a sound just like the record. My first new bird was the chipping sparrow. He had a white eye line and no tree sparrow mark. Saw two tree sparrows and lots of song sparrows too. They seem so friendly back in the bush when they sit singing near you. After that I saw my first northern flicker… then I had a very good look at two and maybe three sparrow hawks. Starlings scattered when one flew to their tree. Killdeers were very active by the creek. A flicker was sitting high in a tree warning everyone I was coming. Heard a couple of birds I couldn’t see. Once a bird rose behind me but my bandana caught on some thorns and I couldn’t turn my head. Guess I won’t wear it again. Got home at nine o’clock and it started to rain just as I got inside.

In the afternoon we all went for a walk down by the bridge and I saw my first phoebe. There may have been a wood peewee there too but I’ll have to check it again now that I have looked it up in Taverner’s (Birds of Canada). To finish the day I saw my first tree swallows sitting on Savages’ wires.

That was a sample of a spring day from my first bird notebook. I kept notebooks sporadically for years but never as religiously as 1955 and 56. For two years I went out almost daily for at least an hour, always with the expectation that I might find something new, see a bird I’d never seen before. By the end of April, I’d seen 55 varieties and was reading about the warblers I could expect to see in May.

In 1955 bird watching was an unusual occupation, especially for a 27-year-old housewife with two small children. Early one morning when I was standing under a birch tree getting its spring leaves and gazing up through my binoculars, a man from the village, taking a short cut along our path stopped to ask what I was looking at. I had to answer – a yellow bellied sapsucker. He didn’t ask me any more questions, but he later asked the village storekeeper if there was anything wrong with Mrs. Deavy.

I was grateful there was one other person interested in bird watching in Navan at the time, Ham (Hamilton) Brereton, a blacksmith who had his home and shop on Trim Road. He called me with questions when he saw his first evening grosbeak because he couldn’t identify it. The May migration time lived up to my expectations. By the end of May 1955, I had seen 85 different birds around Navan. On May 11th alone I had seen 8 new species, all in our back yard. Five warblers, a red-breasted nuthatch, a wood pewee and a chimney swift:

June: Met my first skunk this morning. I’ve always been afraid of this. But we looked at each other and he went one way and I went the other. He looked so sweet, it’s a pity he smells.

By September 11th I saw my 100th species, a Wilson’s Warbler.

That was the fall Judy started Grade I. That made weekends the best time for bird watching. Herbie had become interested in watching for birds as he drove around the countryside each day, being the first one to see a blue bird and a pileated woodpecker. He was the only one to see a red-headed woodpecker. I would still love to see one.

Herbie was quite willing to drive Judy, Andrew and me around the area including the arboretum, and I would make a picnic. We all enjoyed doing this and everyone became more familiar with birds and occasionally added a new bird to the list. Herbie built a purple martin house and put it up in the back yard. It took a couple of years but finally we were successful and had several families of martins nesting in it. The martin house holds several families at a time, nesting and catching mosquitos. Herbie also put up a feeding platform on a pole where we could see it from our sunroom window. We put suet on it for the woodpeckers. One morning we found the platform unscrewed from the pole and lying on the ground, the suet gone. Herbie screwed it on again, put up new suet and once again it was gone in the morning. We decided some village boys were up to no good. I was very angry and decided I would stay up at night, sit in the dark watching. Around midnight when I was deciding to go to bed, I saw our neighbour’s Great Dane coming down the street. He went straight to the pole, stood up and began batting the shelf with a paw until he had turned and unscrewed it. It fell and he left happily with the suet. I don’t remember what we did about it. I do know that Mrs. McFadden was not happy about her dog eating large amounts of suet every night.

One spring morning after both children had started school, which must have been about 1960, I went for a walk in the bush sometime after 9 am. The day was warm and sunny with spring flowers popping up. I was walking quietly along through the woods when I saw on an open sandy area ahead, four fox pups rolling in the sand and having fun playing and wrestling with each other. A hole at the side of the area appeared to be their den. I stood quietly watching. Soon the mother fox came up to them from the opposite direction. She looked at me. It was time for me to leave, going back in the direction I had come, feeling happy and privileged to have seen this family.

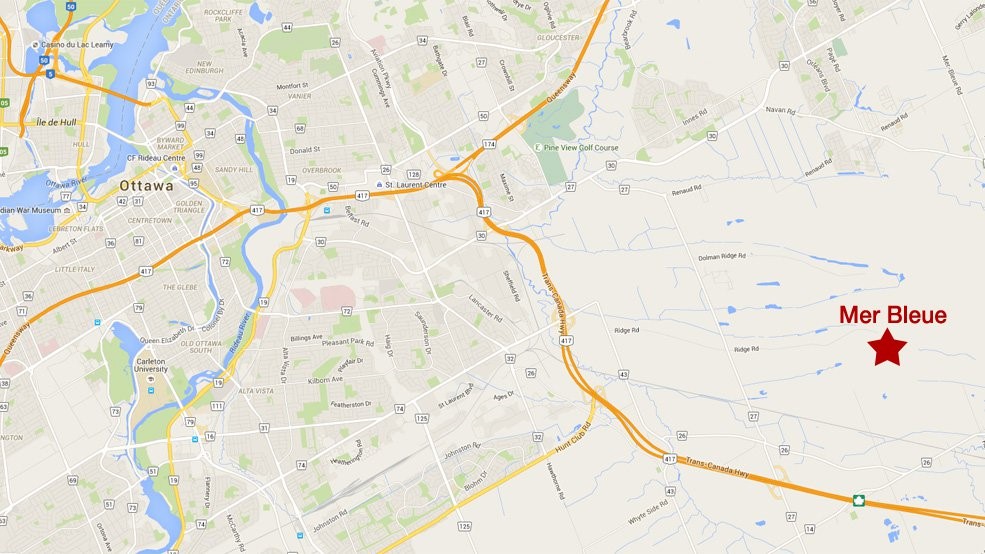

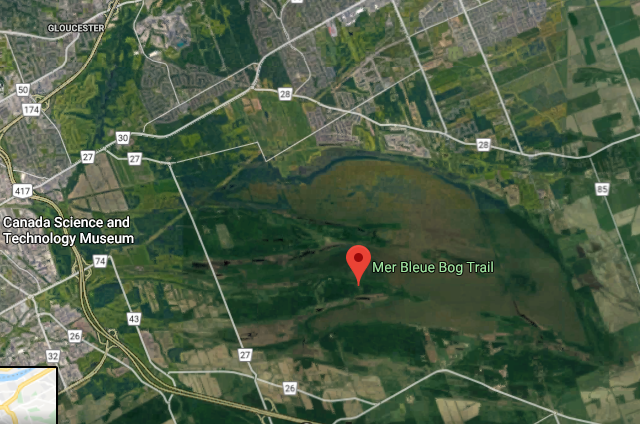

In the fourteen years between September 11, 1955 and April 21, 1969 I was able to add only 29 new birds to the list but my birdwatching got a boost when Andrew turned 16 in November 1968. He was able to take driving lessons through his school and by spring 1969 was eager to follow up on any chance to drive. Judy had been at the University of Toronto for a year and was busy looking for a summer job. I had joined the Ottawa Field Naturalists Club and learned about some different places to watch birds. The Mer Bleue Bog was about 10 miles from Navan and a great habitat for water-loving bird. So every weekend Andrew and I went bird watching.

The Mer Bleue Conservation Area is a 33.43 km2 (12.91 sq. mi) protected area east of Ottawa in Eastern Ontario, Canada. Its main feature is a sphagnum bog that is situated in an ancient channel of the Ottawa River and is a remarkable boreal-like ecosystem normally not found this far south. Stunted black spruce, tamarack, bog rosemary, blueberry, and cottongrass are some of the unusual species that have adapted to the acidic waters of the bog.

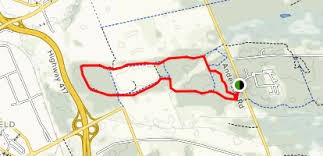

The area provides habitat for a large number of species, including beaver, muskrat, waterfowl, and the rare spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata). A 1.2 km boardwalk allows visitors to explore a section of the bog. There are hiking trails that follow raised areas along the edges of the bog and cross-country skiing trails for use in winter. The conservation area is managed by the National Capital Commission.

The value of this unique wetland was not always recognized. During World War II, the Royal Canadian Air Force used this area for bombing practice. Now, this area has been designated as a Wetland of International Significance under the Ramsar Convention since October 1995.

The name “Mer Bleue” (French, meaning “blue sea”) is thought to describe the bog’s appearance when it is covered in morning fog

On April 27, 1969 we made our first trip to the Mer Bleue and added five new birds to the list. The Anderson Road ran across the western edge of the Mer Bleue with two open water channels running to the east from the road. At the far end of one of these channels you could see a beaver dam. Beavers and muskrats could occasionally be seen swimming through the water as well as many waterfowl. Just inside the fence on a post in a small island of bulrushes, a sign carried the warning that it was illegal to hunt within the conservation area. One morning we saw a muskrat sleeping in the sunshine, right under the sign. The five new birds we saw on April 27th were a mallard duck, a black duck, a pied-billed grebe, a pintail duck and a golden eagle. We had heard that there was a captive eagle near the farthest end of the Dolman Ridge Road which runs along the northern edge of the Mer Bleue. We drove along the Dolman Ridge. There were only a few houses. At the last house we saw the eagle. He had a chain or rope around one leg which allowed him to fly from the tall pole to which he was fastened to the picnic table or the ground. It made us sad to see such a magnificent bird no longer free. We continued our drives until I enrolled in Library School in September 1971 and Andrew was at Carleton University. We added a coot and a Florida gallinule and several new ducks including a hooded merganser, a wood duck and a shoveller. By November 7, 1971 the number of birds seen had grown to 159 (30 new birds in 2 1/2 years) with a mockingbird in our back yard.