Ronnie Deavy on his way to the rink in front of Elsie’s new store, probably 1945

Although we had lived in many places of various sizes, moving to the village of Navan, 15 miles east of Ottawa (now it is a part of the city) in June 1946 was a new experience for my parents, Margaret and me. The village had had electricity just sixteen years. Only four of the houses could boast of indoor toilets. Ours wasn’t one of them. There were two churches, one Anglican, and one United. To find a Catholic Church we had to go four miles farther east to Sarsfield. The language of the parishioners, the priest and the sermon was French. Since the service was still in Latin, it was familiar to us. But the fact that people owned their pews was new to us. Fortunately an English speaking Catholic family, the Grimes’ from Navan were friendly to my mother, Margaret and me, helping us get adjusted; for example, warning us that although it was summer, the priest frowned on women and girls wearing short sleeves. Also they kindly offered us a ride when Daddy was too busy to drive us. There were and are many francophones in Eastern Ontario but at that period they usually lived in separate communities. Most of the francophones of Navan lived west of the village and were market gardeners, selling their produce in Ottawa.

There were two general stores in the village and a smaller grocery and meat store (Lavergne’s). The two general stores were a few hundred feet from each other on Colonial Road. Bradley’s, a thriving store built in 1901, sold groceries and such items as boots, underwear, pots and pans, etc. The other store belonged to Elsie Clarke, an eccentric middle aged spinster. Her father, William Clarke had also built his store in 1901 and Elsie had taken over the management after her parents’ deaths in the early 30’s. The original store had burned in 1943 and been rebuilt that same year with a space for the Royal Bank and two apartments, one over the bank and the second one behind Elsie’s store and living quarters.

Elsie had also succeeded her father in the Post Office. William Clarke had been the Navan postmaster since 1884 and Elsie was postmistress until her retirement in 1967. The post office was at the back of her store, and she could usually be found there with mail bags all around her. She knew everyone and everyone knew her. Unless you were on the rural mail delivery you went to the post office every day to get your mail. You didn’t often go to Elsie’s for actual groceries because most of the items on the shelves looked as though they had been around since before

the fire. The variety of items was amazing, ranging from mousetraps to Miner’s liniment; the latter was a strong smelling ointment she believed prevented sore throats and colds and it could usually be smelled in the store. Elsie’s father had invested in land in and around the village which now also belonged to Elsie.

Elsie owned the house in which we were living. It was known as the Visser House and was one of the oldest buildings in Navan. A two story frame covered log building, it had been built in the 1860’s at what is now the corner of Trim and Colonial Roads by Captain Herman Visser for use as a house and a store. William Clarke bought the house in 1893 and in 1901 had the building moved east from the corner so that he could build his new store in its place.1 Elsie had lived in the Visser House and set up the post office there after the 1943 fire until her new building was finished. The house had also been used as a barber shop. When we moved there the house had been made into a two family dwelling. We lived on the left side and Mrs. Annie Morison, an elderly widow, and her son Lloyd lived on the right side. Lloyd had served as an air force navigator throughout the war and now worked for Bell Telephone. We shared a wide verandah across the front of the house. Our front door opened into the living room with the stairs to the second floor on the right. The large kitchen was across the back part of the house with a door to the back yard where a large garden was shared by the two families. Behind the garden, a long shed served both families as a storage shed, a shelter for firewood and a shared outhouse. Someone had thoughtfully pasted some interesting news stories, such a VE day celebration on the inner walls of the outhouse. It also had its seat cover, its pile of carefully torn squares of newspaper and its pail of ashes for sprinkling on the contents. Margaret and I usually accompanied each other out there with a flashlight at night.

Elsie had had the inside of the house wall papered and painted before we moved in. They were actually finishing up the day we arrived. She also provided us with yellow paint to give the outside a fresh coat. Margaret and I with Daddy’s help worked away at it that summer. Margaret and I were spending more time doing things together that summer since neither of us had yet found friends our own age. Sometimes Mrs. Morison invited us in for a visit. She liked to show us her photograph albums of pictures of her several sons and daughters who had married and moved away from Navan as well as pictures of Lloyd, her youngest, in his uniform and overseas. While we looked at the pictures she served us cookies and dishes of preserved raspberries. On Sundays Elsie took us for rides around the country side in her Model T and we visited some of the farm houses, where she always seemed to be welcome. The rides could be a little nerve wracking because she occasionally drove on the left side of the road. But fortunately there wasn’t much traffic and she drove slowly. When we got back home she would invite us into the store and heat up a can of Habitant pea soup which we ate out of cups. Elsie would also include us in her evenings at the movies in Ottawa. She arranged with the owner of a station wagon to drive 5 or 6 people to see a movie at the Capital or Regent Theatres. Afterwards we might go to the Honey Dew Restaurant before our driver arrived to take us home.

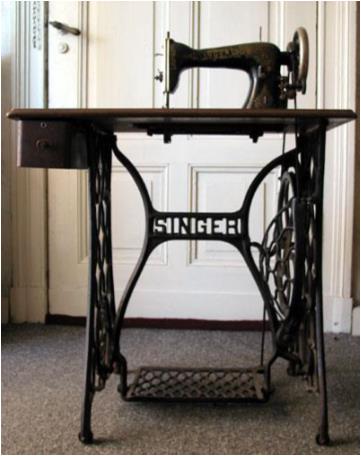

With Elsie’s help I began to sew a bit that summer. My mother learned that an old girlfriend of her brother Artie was working at Murphy Gambles (a department store on Sparks Street) in the dry goods department. When we went to visit her there, she showed us some pretty taffeta material that would make lovely summer skirts – pink for me and yellow for Margaret. She assured me the skirts would be quite easy to make, – a simple buttoned waistband, with the skirt gathered on it. Elsie let me sew the skirts on her treadle sewing machine. Mom helped us hem them and soon Margaret and I were enjoying the new skirts.

Margaret & Betty in Elsie’s yard on a teeter totter. Margaret is in her new yellow taffeta skirt, 1946

A treadle sewing machine ran not by electricity but by foot pedals which you moved up and down as you sewed

The Dunfields and the Lancasters lived in the two apartments in Elsie’s building. The Lancasters had a little girl about 3 or 4 named Sandra and the Dunfields had three children; an older girl Elizabeth, about 10, a younger girl Sally, the same age as Sandra and a boy Sammy, a cute little red headed child about 2. Margaret was always very good with little children and soon was the unofficial babysitter and mother’s helper to them, especially Sandra and Sally who followed her all about. They could often be found sitting on our verandah with Margaret reading to them or playing games.

Mr. Dunfield owned the telephone company in the village. In the 40’s small individual companies existed although I think they operated on Bell lines. The telephone switchboard was set up in the front of the large cement building that had been the cheese factory. (It had closed during the war). Several of the local women worked at the switchboard over the years and performed an essential service in the community. Mr. Dunfield suggested that I might like to learn to operate the switchboard. I could then act as a substitute over the two hour supper period between shifts of the regular operators. I agreed to try. It sounded quite simple. I don’t remember how much training I was given before I was left by myself, but it wasn’t enough. As I remember, you sat in front of the large upright switchboard, which was covered with plugs, one for each number.

The numbers represented the individual lines. I don’t remember what our number was but Deavy’s was 5. It must have been very early. You had to plug into the flashing light, find out what number the caller wanted, then plug into the number and ring the appropriate number of rings, if it was a party line, which most of them were. If it was a long distance call, you plugged into the connection with the long distance operator. Meanwhile more lights were flashing on your board that you were unable to get to. I kept trying to go faster but could not catch up. The two hours seemed like a nightmare. By the end I was ready to collapse and felt quite feverish. I had great admiration for our local operators ever after but never tried it again. Mr. Dunfield offered me an alternate job of sorting out long distance charges for the monthly bills. I had more success with that job.

Meanwhile our father had begun practising medicine in the community. Doctor Irwin had been killed by a train at a nearby railway crossing two or three years earlier. His wife and family still lived in the village. The nearest other doctor was francophone and living in Orleans. Several of the women in the community had been nurses before their marriage and they provided informal health care, being called on for first aid and to assist in illnesses and with new mothers. Daddy appreciated the help and advice of Henrietta Lancaster, a village nurse, as I did in later years.

Daddy’s office in Navan was in the living room of the house. It must have been difficult for him although I wasn’t aware of it then. As a country doctor his patients were of three types:

- those well enough to come into the office, with chronic illnesses, rashes or colds or needing first aid for cuts or breaks or insect bites

- those patients requiring home visits for more severe illnesses. It was before the polio vaccine had been discovered and there were occurrences in the community. If patients had to be cared for in the hospital, he often took them himself.

- Then there were accidents which could happen at any time. The first month we were in Navan, he was called to attend a farmer who had fallen from his barn roof.( Doris’ brother George Cotton) The man lived but spent the rest of his life in a wheel chair.

Daddy spoke little French so language was another problem. Although most of the francophone men were bilingual, many of their wives spoke little English. It was amazing that he could discover symptoms and treat patients with a minimum of dialogue.

I guess they had some sort of universal means of communication. We knew the visit had come to an end when we heard him say “Tout fini” a phrase I always associate with him. Most babies were born at home in the forties and he was often called to the birth of a child at a francophone home. A few of the market gardeners have told me they remember Dr. Joyce being at their home when their brother or sister was born.

Even though we didn’t own the house, Daddy began doing some major renovating on our half of the log building. He and Elsie got along well and she was agreeable to the changes he suggested. By the end of the fall he had built a stone chimney on the west side of the house and a stone fireplace in the living room. He seemed to feel the need of this sort of activity while waiting for patients or the phone to ring for an emergency.

Between our house and Bradley’s store was the Anglican Church Hall, a grey wood frame building. It had been owned by the Independent Order of Foresters and was still called Foresters’ Hall.

The IOF or Independent Order of Foresters, a fraternal organization founded in the 1800’s that working men might help each other also offered insurance to the members. It would burn along with Bradley’s store two years later on August 28, 1948.

Frequently on Saturday night there was a dance there, sponsored by the church. Someone, I don’t remember who, encouraged me to go, saying I would enjoy myself and meet some of the local young people. I agreed, since any social event was beginning to look attractive, although I didn’t consider myself a very good dancer. Margaret had always been the dancer in the family and loved it since her tap dancing days in Cargill. The dance started at about 8:30 or 9:00 when the small local orchestra, a piano, a violin, a guitar and perhaps a bass fiddle would set up on the small stage at the front of the hall. At least one in the band would sing. Straight back wooden chairs placed all around the walls of the hall soon were filled by girls and women of all ages. Most of the men and boys stood in groups at the back of the hall. I think the admission was about 50 cents. I remember sitting and talking to Lydia McCullough who had befriended me, while other people began to dance. I was quite popular, to my surprise and was asked to dance by a few of the young men. It helped to be eighteen and a new face in town. I was persuaded to try a square dance for the first time. It was fun although fast and confusing trying to follow the commands. Thank goodness, the other dancers were patient and experienced.

Good square dance callers were highly prized at these dances, those who had a large repertoire of calls and dances. Sometimes the band brought their own caller and sometimes one was chosen from among the dancers.

The dance lasted until about 11:30 at which time the Anglican ladies served a lunch of small sandwiches, cookies and squares with coffee and tea. Alcohol wasn’t consumed at these dances that I was aware of, although in later years, at other dances in neighbouring villages I knew people went out to the parking lot to drink.

One of the young men I danced with was Lydia McCullough’s brother Wes. They lived on a dairy farm east of the village. Wes was planning to go to Queen’s in the fall. Meanwhile he was joining a group going on the harvest train to Saskatchewan to earn extra money for his education by helping western farmers bring in their harvest. There weren’t as many machines to do this work then. Before he left Wes thoughtfully offered to loan me a box of books he had collected for his university course. Among the items in the box were all of the plays of Shaw. There was no library in Navan and it was not easy to get to the public library in Ottawa. I appreciated his offer of so many books. He later became an excellent high school teacher. I recently learned this from a friend who was his pupil at Lisgar High School in Ottawa in the 60’s.

Great recall. Reminded me of my youth, Betty. I lived in Timmins and our outdoor toilet was in the bush across the lane at the back of our home. Night times mom had a pink container for us to use. One day when I was lining up with my class, the mum watching over us,pointed to me. She told me to go home and change my sleeveless blouse. I ran home crying! I must have been about12 years old.

So interesting to hear the history of Navan. Thanks for putting this excerpt in. It made me laugh and remember lots of events in my lifetime.